It might not be a party trick that makes you many friends, but it can be useful to remind yourself, periodically, that your life will end. You will lose everything and everyone you have ever known or loved, and then you will die. Every friend you have ever had, every colleague, every person that you pass on the street, will also lose everything and everyone they have ever loved, and then die.

The Stoics routinely rehearsed the deaths of their loved ones as a form of psychological immune building. The idea is that if we can imagine the bottomless pain, despair, and hopelessness of losing our nearest and dearest on a regular enough basis, we might just be able to face the depths of that pain and despair when they inevitably come knocking.

But who wants to sit with their cup of coffee in the morning and think about holding grandma’s hand in the hospice as she takes her last breath? Our modern lives are often too busy, too stressful, too emotionally curbed, too sanitized and too comfortable to entertain the idea of negative visualisation. But this is, of course, what we were all asked to do, every day, at the beginning of the pandemic in March. Press briefings and news desks plastered the numbers of the daily dead across our screens as we were eating breakfast or getting ready for bed. Models and graphs warned of unimaginable numbers of lives lost. Boris Johnson ‘levelled’ with the British public by telling us that ‘many families are going to lose loved ones before their time’; a Stoic statement from the Oxford Classics graduate.

But this Stoic strain didn’t last for long. Rather than the calm, composure and resilience that the Stoics advocated in the face of the tragic inevitability of human death, the British government whipped the public up into a frenzy. Panic buying, stockpiling, mast-burning, general fear in the eyes of the dog walker who circles around you a little further than is necessary in the park. It seems that the contemporary British public is more than a few steps removed from the society which ‘kept calm and carried on’ during the Second World War.

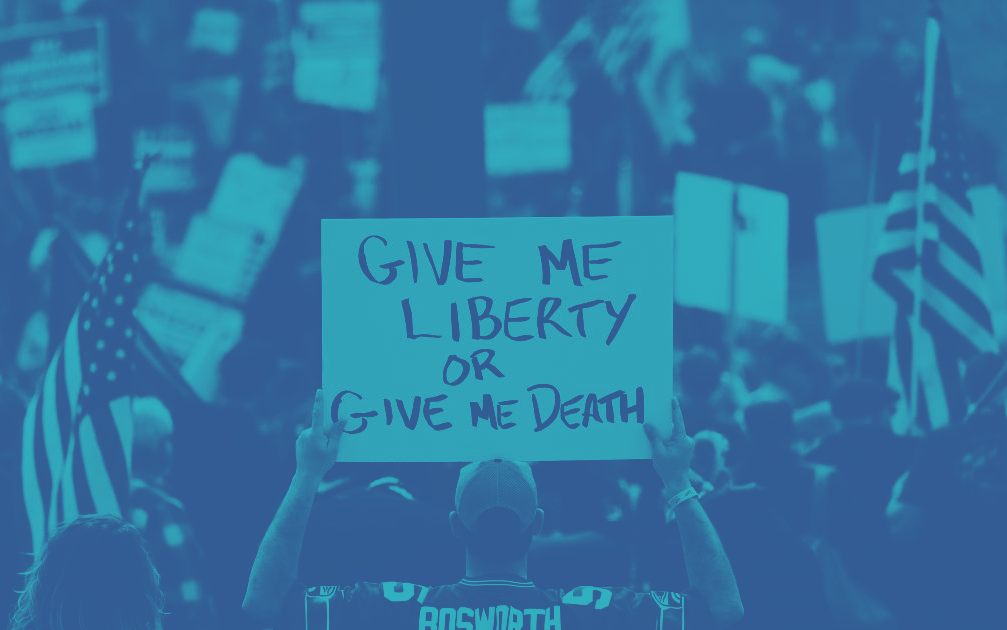

We were told that our freedom and normal way of living were a price worth paying for the preservation of life. To argue otherwise, as the government seemed to whilst pursuing their ‘herd immunity’ strategy in the heady, pre-lockdown days, would be to out yourself as an evil, totalitarian monster; a tinpot Mussolini hell-bent on the reduction of the world population. The ‘lives vs. livelihoods’ false dichotomy, the logical fallacy of which is too obvious to bother unpacking, aimed to shut down any criticism of the lockdown strategy. But it also revealed a deeper, more potent anxiety in our society; our inability to grasp and accept the realities of death.

The Stoic principle of negative visualisation aimed to conquer the fear of death; it recognised that something so deeply painful, disruptive, and yet unavoidable, could not afford to be brushed under the carpet and thought about at a later date. The Stoics positioned death as the focal point of life; the undeniable force that gave meaning to our short-lived time on Earth. They encouraged us to live under the shadow of death not for morbid or melancholy reasons, but in order to motivate us to live each day with mindful attention, urgency and perspective. For many of us lockdown was a chance to do this. The early days gave us time to slow down, reflect on our lives and connect with the ones we loved: call them more, spend more time with them, tell them we appreciated them. But the lockdown strategy takes as its basic premise the fallacy that death itself can be conquered. If we only stay far away enough from each other, locked up in our homes, isolated from a society that has ground to a halt, then we can all become life-saving superheroes.

There is an enormous level of hubris and denial wrapped up in the idea that an elected government can ‘stop the spread’, ‘save lives’ and ‘control’ or even ‘eliminate’ a novel virus. The sentiment is a natural product of our current technological and medical sophistication. We can now nurture babies born 6 weeks prematurely to grow up into healthy adults. We have the medication that allows a person with AIDS or Stage 4 cancer to live a long and fulfilled life. We can transplant organs into dying patients or even, with developing STEM cell technology, regrow those redundant organs within the patient’s own body. So it seems natural that a society competent enough to perform these feats, which would have seemed like the darkest sorcery to those living even 100 years ago, would think itself capable of ‘stopping the spread’ of a new strain of coronavirus.

All of the messaging around the lockdown is underlined by this hubristic, modern belief that illness, disease, or death itself should not prevent us from living long, healthy, comfortable lives. It leads to a deeper, even more unrealistic idea that death is in some way a failure of modern medicine; we no longer frame death as the inevitable outcome of living, but instead as a nuisance that will soon be eradicated by technological progress.

There is nothing wrong with these utopian beliefs. They are the natural outcome of an increasingly technocratic and medicalised culture. I am incredibly grateful to live in a world that may well find a cure for cancer in my lifetime. It is of course a spectacular feat of modern technology, and a stunning affirmation of the value of human life, that we are able to spend so much time and energy helping those with the most difficult diseases or conditions to live fulfilled, pain-free lives. To us in contemporary society, all of life’s ills seem conquerable enough, including the final one, death. If it isn’t right now, it will become so soon.

Death is no less tragic because of its inevitability, and to accept that death happens is not to pretend that it isn’t the most painful thing that a living person could experience. Of course death is awful. And there is perhaps something particularly, cosmically cruel about losing a loved one to a disease like cancer or COVID-19. How arbitrary, how futile, that a perfectly healthy, good person should be struck down by the cruel and faceless force of nature. Even the most staunch anti-lockdown activists are not impervious to grief, or unaware of the unbearable tragedy of a lost life. But to pretend that death will not force its way into your life, or that a strong enough government strategy can prevent it, is naive and childish.

The revolving door of lockdown strategies in the West shows that we are still incapable of having this grown-up conversation about death, despite how prevalent the subject has been in 2020’s cultural conscience. The point of negative visualisation for the Stoics was not to dwell on the sadness of death, and let it plague our waking hours, but to bring a sharper focus and clarity to the everyday. Reminding yourself of your mortality was supposed to invigorate you to live every day with purpose, in full awareness of the fact that it could be your last.

But lockdowns strip us of the freedom to look at life in this way. It is a sitting-duck approach, forcing us to cower in fear from the realities of death or the discomfort of illness. The things which usually make life worth living – seeing friends and family, work, socialising, eating great food, visiting new places, engaging with the arts and culture – all of this has been taken away from us while we sit and wait to die a death that our society is pretending will never occur, if only we can sit and wait a while longer.

When we get back to being able to do those things we should do so with a sharper attention to the transitory nature of our experience, and a greater bravery to attend to the things in our lives that we fear to lose. For we will lose them. And there is nothing to be gained from pretending otherwise.